Stephen Burke

Stephen Burke is a fine-art painter from Dublin who now lives and works in Glasgow. Having studied Printmaking at NCAD and receiving a masters degree in painting in Glasgow in 2018, Stephen now produces work based on the urban environment.

In particular, Burke has focused on the art of graffiti removal known as ‘buffing’. Along with photographer Fiachra Corcoran, Stephen documents the systematic removal of graffiti in Dublin by the Dublin City Council and private homeowners. Burke has described these coverups as art in their own right, noting their ambiguous nature as “public art, socially engaged art, collaborative art, street art, graffiti”. From photographs taken of these ‘buffs’ Stephen creates his own paintings and sculptures using related materials such as aluminium, emulsion and spray paint.

Selection of work from ‘Merkland Street’, 2018. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

How did you get started?

I originally got started through graffiti. There were a few local pieces in the area that I grew up in that I remember standing out, Phats, MSO and Grift had some chrome dubs. I was quite drawn to it at the time. It seemed counter culture which was appealing. It feels less like that now due to how the subculture’s been pushed in mass media and used by ‘edgy’ companies but I guess all these phases play a part in its evolution. Artists need to get paid and these avenues seem to be successful in doing that. I got interested in contemporary art soon after and eventually went on to art school which was great. I’ve met some cool people while studying.

In an interview in late 2018 you mentioned ideas you were currently exploring; Public vs. Private Spaces, Post Vandalism, Anti-Landscape Painting. Can you elaborate on these?

When referring to public vs private I mean that in regards to the context of production. An artwork made in the privacy of a studio will vary greatly to a work made in the public realm. The work I’ve recently been making relates to the architecture of Glasgow and some of the public spaces it presents. For example, a unique characteristic of Glasgow are the tiled interiors in the communal hallways of the tenement buildings which house a large portion of the city. In the 19th century Glasgow had a reputation of being highly unsanitary and was being overrun with poverty and disease. The cities Improvement Trust Campaigns in the 1870s triggered the beginning of huge social and sanitary reform. One of the big aspects to this reform was tiling the communal hallways of the tenement buildings so that they could be easily cleaned and to prevent disease from spreading. The fact that many of the tiling patterns were aesthetically appealing was originally incidental, their core purpose was to contribute to the cities reform at the time. This later changed when tiling designs became popularised and eventually showed a sign of wealth with many expensive butchers and fish mongers in the city sporting their own unique tiling patterns and images. These beautifully crafted tiled walls began feeding into my interest in graffiti, particularly places like train stations where scrawls can commonly be found. The hyper clean tile interiors of subway stations have always been romanticised to writers via the subway painting videos from mainland Europe that flooded youtube years ago. Traditional painting videos like ‘Dirty Handz’ comes to mind but probably more applicable is ‘Territorial Pissings’ by Nug, although I believe this was obviously a step away from conventional graffiti.

‘Berlin’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

Post vandalism is a term I would like to push a bit more, maybe even champion someday. It so accurately describes the residual buff paintings made when graffiti is removed. It also perfectly describes the variety of artists who come from a graffiti background but are now working within contemporary art. I’ve been meaning to make a book documenting this for some time as there’s lots of artists who are taking from the ideas of graffiti and translating them into contemporary works. Rafael Schacter's 'Streets to Studio' is a great book that discusses how traditionally, tagging was too low brow for the art world and muralism was too accessible. Now, there’s lots of great concepts coming from people who formerly wrote which challenge the conventions associated with graffiti in the art world. Look at Igor Ponosov for example, he’s made some intriguing works on the commodification of anarchy or Brad Downey who interrogates themes around accessibility which is an issue commonly found in graffiti, on the internet and on international borders.

‘Glasgow’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

How were you introduced to Buffing and the Art of Removal?

Fiachra Corcoran and I began looking into it around the same time during our art school education, maybe 2013 or so. It began as a simple aesthetic acknowledgment, the painted grey shapes created as a result of removing graffiti looked like many of the artworks created within the abstract expressionism or minimalism movements. When we stumbled across Avalon Kalin and Matt McCormick’s movie ‘The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal’ we were really blown away. Whatever notions we were having about these buffs seemed to have been legitimised and expanded upon on a much higher intellectual level than we could have imagined. Soon after we began our ‘Buff Publication’ project and started looking at graffiti removal through a more academic lens. We wanted to build on what Avalon and Matt had made with their original documentary so we began conceptualising some of our own ideas. We coined the terms ‘Etched removal’ and ‘Maltreated removal’ during this project. An etched removal relates to the removals carried out with sand blasters or pressure sprayers, these can be some of the most subtle works but can also do permanent damage to the surface they're used on. When applied to brick or concrete the strength of the pressure sprayer can etch the surface if used incorrectly. While this obliterates the graffiti once present it also eats into the wall creating a shadow where the graffiti once was. Despite the unconventional medium, these marks can often resemble very basic painterly compositions. A maltreated removal is exclusively created by property owners and DIY removalists. Often these removals are spray painted and look quite aggressive. They involve a rough scribbling out of graffiti. They’re most commonly found in working class areas and the aesthetic is typically grimey and unpleasing. They are often used to cover up offensive graffiti – racist or abusive tags – and are clearly formed out of haste to get rid of the scrawls. Although they do cover up the original vandalism, they often look equally distasteful.

‘Dublin Docklands’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

We also began conceptualising some ideas around the locations that buffs can be found. As it turns out there was evidence in our research that the socio-economic makeup of an area affects the types of graffiti removal found there. This allowed us to look at buffs as signifiers for the socio-economic background of a place. Generally, the looser and more chaotic looking buffs were found in working class areas and the tidier ones were found in upper and middle class locations. Perhaps this is a comment on how certain areas are looked after more so than others but more than likely it comes down to DIY culture. The vast majority of the messier looking removals are created by property owners who want to get rid of whatever vandalism is on their property asap, this means they’ll probably use what tools they already have to remove the scrawls. Paint colours are rarely matched in these instances and the resulting removals often fit within the maltreated removal bracket and appear similar to paintings by the likes of Franz Kline. Avalon had some interesting theories around this, he argues that society is so creatively repressed that sometimes our visual culture is communicated to itself subconsciously, whether there’s truth to this statement is up for debate.

‘Southside Suburbs’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

In relation to Buffing, I see you have mentioned Abstract Expressionism as well as referenced Situationism. I would argue that your work on Buffing also plays with concepts of Urban Dadaism & Anti-Art, as you question what is considered art in the public space and who the artist is. Can you elaborate more on how these concepts figure into buffing, your research and subsequent art produced.

When you focus on buffing as an artistic practice it begins to blur the boundaries between what is generally considered fine art. It draws a line between highbrow and lowbrow art, between painting and vandalism. It raises questions around ideas like outsider art, labour art, subconscious art, information theory and censorship. In relation to abstract expressionism, the similarities are only on an aesthetic level, the spontaneity of that movement isn’t mimicked in graffiti removal. These removalist paintings have a very definite purpose and guidelines to how they should be produced (trace around the graffiti), they’ve got a blueprint. Abstract expressionism is quite different in that way, it's more about gesture and intuition.

‘Southside Suburbs IV’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

The situationists have always been very interesting to me, they were a group of social revolutionaries from the mid 20th century who explored ideas around anti-capitalism amongst lots more. In the way that graffiti removal as an art practice relates to situationism it also relates to dada, both movements possess a level of satire and rebelled against traditional artistic values. Détournement was an idea associated with the situationists that subverted the expressions of the status quo against itself. In many ways looking at the censorship of graffiti on a creative level subverts in a similar way. Psychogeography is another theory which was defined at this time by Guy Debord. This was a strategy to help the public navigate their urban surroundings in a new way through dissolving the partitions between art and life. He hoped this would draw people to travel new routes due to a new awareness of their surroundings. I use these strategies to search and document buffs and other street anomalies regularly, its an essential part of my practice that I find quite therapeutic.

‘Crumlin’, Oil and emulsion on steel, 64 x 76 cm. Photo credit: SO Fine Art

Can you take us through your art making process?

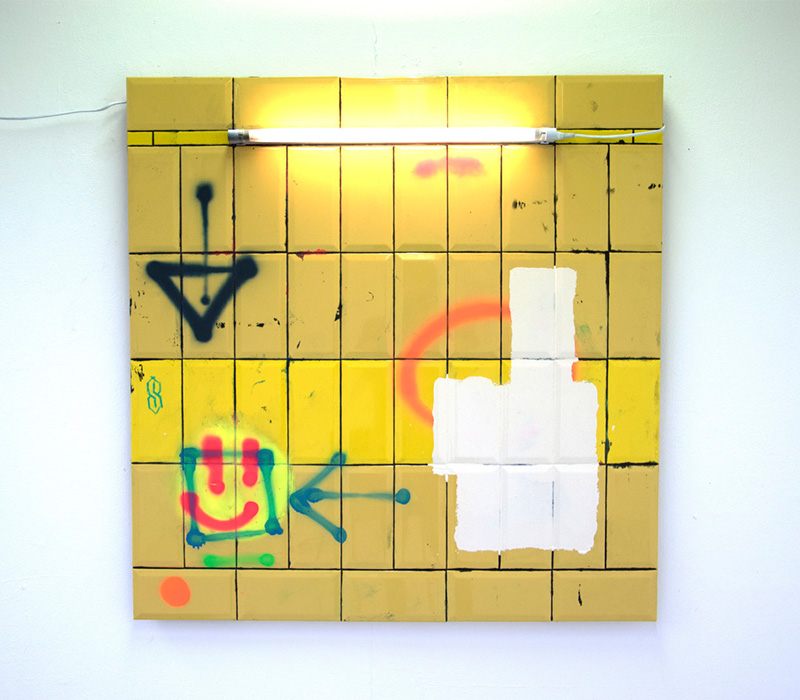

Depending on the context the process changes a bit but for the most part I’ve been making studio works recently. The process usually starts through exploring new places and gathering documentation of anomalies or patterns found there. A common theme which keeps appearing lately is the pattern of gentrification. More construction hoardings, sterile glass tower blocks, skyline cranes and road works all signalling the demise of an area with any cultural value. A recurring aspect which I kept noticing in Glasgow were the spray painted line markings on the ground which directed the construction teams to segments of the road where they could lay new tv lines and pipes. Generally, they’d be signed with the companies name and a number, for example, ‘BT 356L’. Mike Ballards has an interesting theory that the rising number of these road markings is indicative of a population increase in that area, perhaps there’s an element of truth to this as most of the places you can find these markings in seem to be trendy, ‘up and coming’ areas. I wanted to combine some of the road markings I had documented with an older element of Glasgow, its tiles. At one stage the introduction of these tiles was a sign of change and social reform, I guess there’s some parallels in these road markings too. Once I’ve gathered enough documentation I’ll start making some works.

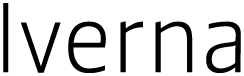

‘Maryhill’, Mixed media on ply, 105 x 100 cm. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

The works I’ve made recently began with me learning how to tile. I wanted to construct a surface to work on that related to the urban environment. For me canvas has always seemed a bit inappropriate to convey what I’m trying to say. I’ve always been attracted to working on unconventional materials and canvas never fit that bill. To be honest I can’t remember ever painting a canvas, it's never carried the same lure as steel, wood or tile. When I’ve constructed a surface I’ll set about integrating other utility elements that can be found in public spaces like street lights or handrails. The handrails were something new which I gathered an interest in through some of the bath houses here in Glasgow, they have some beautiful tiled interiors with raw steel handrails. Some of the handrails were also referencing the steel rung ladders seen in service chutes used by graffiti writers to access subway tunnels in videos online. These chutes are often displayed with steel rung ladders which descend onto the tracks below. Next, I can begin painting the surface. This is usually a process which takes reference from street photos and typically involves a lot of addition and subtraction of marks. Having an interest in graffiti removal has helped with the subtraction, usually I can edit marks out without much trace. This part of the process can take a while, the painting won’t be complete until the composition feels correct which can take a few hours or a few days.

‘South Side Suburbs’, Photograph. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

‘Ballymount’, Polyurethane and oil on aluminium, 2017. Photo credit: SO Fine Art Prints

As you have explained, the imagery of construction markings was incorporated into your own work. Though I'm sure there are an endless amount of concepts derived from urban development, is the concept of construction markings an area you want develop to a further extent akin to your research, publications and work on Buffing? It seems to bridge the gap between 'tagger' and 'buffer', as they are labourers not artists making additions to the urban environment with similar material to graffiti artists and in some sense are signing their work with names that could also pass in the street art world.

Yes, I’d love to! There’s been some work made about the construction markings I’ve seen online but perhaps nothing too academic as far as I know. If it is to be believed that the markings are signalling population increases and gentrification then it could be linked into existing socio-economic issues. As it so happens sometimes there’s an overlap between the workers who create the construction markings and buffs, the buffs will typically be DIY in these instances as the labourers main job is within construction. You could classify these workers as outsider artists, although they appear unaware of their works relation to traditional fine art. Avalon Kalin developed a nice format for academicizing buffs that could be used on these construction markings. It would take lots of documentation and some careful examination but I’m sure there’s some aesthetic patterns in these markings that could be used to categorise them into groups. I’d like to make that a project for 2019. If there’s any designers interested in collaborating on a book hit me up!

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

I’d like people to take notice of their surroundings more, especially in urban settings. There’s lots to see once you begin to deconstruct the traditional ideas of what art is and where you can find it. There’s truth to the theory of ‘life imitates art’. Our built environment is shifting so quickly nowadays, it’s important to acknowledge change within our habitats as it can have a real effect on our psyche. Having said this, I don’t want the work to be conclusive as its potential to be interpreted in a new way becomes limited. There has to be a level of ambiguity for it to be interesting. When a pieces meaning is obvious that’s all it is, it can’t go any further. There’s themes of gentrification, transgression, utility, labouring and typography among more. I’d like the works to be looked at through these lenses but to remain open ended.

‘Bath House’, Mixed media on tile, 122 x 120 cm, 2018. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

How much of your work is research and how much is practical? Was research an aspect of your studies or was it something you pursued yourself?

I invest a lot of time into reading about the topics I’m interested in. I enjoy doing it so it never feels like a chore, it's fun! There was research within my studies with dissertations to write and things like that but for the most part I’ve taken it upon myself to absorb as much as I can about these themes. For a while research was all I was doing due to not having a studio for a couple of months before I moved to Glasgow. I think they’ve balanced out a bit in the past year due to the practice heavy masters I’ve just finished. Buff as a project really straddled the line between research and practical. For me, its essential for a work to have both. I’d like to produce some more books in the coming years, books that touch on academics but also carry their own innate aesthetic values.

What other techniques do you use?

I just finished up a masters at the Glasgow School of Art so I had access to lots of great workshops up until recently. I constructed the handrails used in my paintings through using a plasma cutter, steel tube bender and welder. Welding was a particularly fun technique, definitely a process I’d like to work more with. I did my BA in printmaking but Its been awhile since I’ve printed anything. I want to change that this year though, I’d like to release 1 or 2 screen print editions in 2019.

‘SSS/SY’, Mixed media on tile, 160 x 120 cm. Photo credit: Stephen Burke

How do you challenge yourself artistically?

I’d like to challenge myself this year by having solo shows at home in Dublin and in Glasgow. I haven't showed work in Dublin for a while so it’d be good to get back there and do something. I’m going to begin some video works this year too, no doubt learning how to edit will be a challenge. I find traveling helps me creatively a lot, it shows me I’ve lots to learn. Staying in the same place too long can get stale and new perspectives are important. I’m heading to Copenhagen in February, it’ll be my first time in Scandinavia so I’m looking forward to that. There’s such a vast history of urban art there. I’ve a good buddy I met at art school here that’s just moved back to the states, I’ll probably head over to visit him at some stage this year too.

To see more of Stephen Burke’s work visit: stephenburkeart.com · @stefano.bardsley